The bankruptcy means test was established by congress as a standard method of calculating the disposable monthly income of a debtor, to help determine the amount paid to the trustee of a Chapter 13 bankruptcy plan.

We recently discussed several aspects of bankruptcy with Christopher Holmes and Jess M. Smith, III, partners at Tom Scott & Associates, P.C. The discussion covered several topics, including the means test, the differences between Chapter 7 and Chapter 13, how divorce and child support can affect bankruptcy, and the discharge process. Below is Part 1 of 4 of the transcript of that conversation.

Q: In a Chapter 13 bankruptcy, how is a debtor’s monthly plan payment amount determined?

Chris Holmes: In a Chapter 13 bankruptcy case, the general rule would be that the debtor must pay to the Chapter 13 trustee all of their disposable monthly income. So, we craft their budget to show how much their projected monthly income will be—gross income minus taxes—and then we calculate what they pay for rent, utilities, food, clothing and all of their living expenses. So, income minus expenses, whatever that difference is, that’s the primary way of determining the monthly plan payment. The bankruptcy code says a debtor must turn over all of their disposable income to the Chapter 13 trustee for the benefit of their creditors. And then, as long as they’re not already paying off 100 cents on the dollar, that’s what they have to pay.

Q: How do factors such as everyday expenses figure into determining what a debtor’s disposable income ends up being?

CH: Whatever their real expenses are or there are some IRS standards that we use on occasion. Obviously, a family of eight has expenses that are greater than a family of three. Jess and I have been doing this for so long, we understand, after putting thousands of budgets together, how far you can push the envelope on a food budget, for example, for a family of four. We know that if we go beyond a certain amount—a sort of comfort zone—that the trustee gives us some pushback and says, “Wait a minute. $1200 a month for two people?” So, for example, they can’t be going out to St. Elmo’s Steakhouse every night for dinner. They have to be reasonable in their budget. We’ve learned over time what a reasonable budget is, based on the household size.

The general rule of whatever is left over goes to the trustee was thrown out the window in a recent case we handled, because the husband had a job and the wife was disabled. She received Social Security benefits. Their combined income, including those Social Security disability benefits, exceeded their living expenses by $660 per month. Before the bankruptcy code changed back in 2005, and really up until just recently, their plan payment would have been $660 a month. However, in this case, our associate attorney Andrew DeYoung said we are only going to offer $250 per month. The concern was that the trustee would ask, “What about the other $410?” However, Andrew understood that there is an area of the law developing where judges have decided that because Social Security benefits are exempt—off limits to creditors—and that they don’t count in the means test that determines household income.

Q: So, Andrew was subtracting the disability payments from the means test equation?

CH: The wife collected about $1600 a month in Social Security benefits. Andrew was just arguing that not all of the couple’s disposable income should be turned over to the trustee, because the disability benefits are intended to provide the wife with a safety net, in case her health deteriorates or an unexpected medical situation arises.

Q: In this case, had both the husband and wife declared bankruptcy?

CH: Yes, it was a joint case. When the trustee asked why I only offered a $250 monthly payment, I stated there is some existing case law that suggests creditors cannot claim bad faith or abuse when debtors do not turn over all of their disposal income, because some of it—not all of it; just the disability benefits—is exempt from creditors. The trustee stated she was also familiar with that case law, so she dropped that disability income from the plan and, to our clients’ pleasure, accepted the $250 per month offered. I asked her if any Indiana judges had ruled on this type of situation or if there are any related 7th Circuit Court of Appeals cases. She stated not to her knowledge. The precedent for this is from some other jurisdiction where crafty bankruptcy lawyers have made this argument and evidently those judges have agreed, so she’s basically taken a position that maybe it isn’t money that she can demand from the debtors.

Q: You mentioned a family of four, which obviously includes children, and a related comfort zone of credible monthly expenses. Is there any entertainment budget that you can justify as not part of that family’s disposable income?

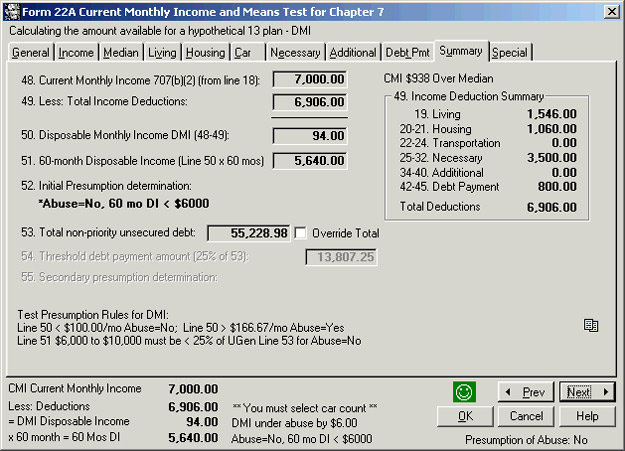

CH: There’s two things. There’s the means test, which looks at average monthly income over the past six months before filing. There’s also certain IRS standards for housing and food and whatever. If I refer to the computer program we use, I can look at how much is deemed to be reasonable for a four-person household. So sometimes when my clients don’t do a really good job on their budget, I’ll go to the means test and use the IRS standards to fill in a blank. Also, if a debtor shows too much money left over, and I know they really don’t have it, I’m going to find some place to use up that money, so they’re not too rich for a Chapter 7 bankruptcy. There are standards for what you can put into the different slots within a monthly household budget.

Q: Where do you find the means test you mentioned?

CH: It’s something that congress established, but our computer program provides all of this information, which is periodically updated. In Indiana, there’s currently a medium income for a one-person household of $43,422.

Jess Smith, III: The medium income varies from state to state.

CH: That’s the starting point. So if I have a family of four and their household gross income per year was less than $74,584, they immediately pass this test. The test is designed to determine if someone has an ability to pay back a significant percentage of their debt through a Chapter 13 plan.

Q: What happens if they fail the test?

CH: They’re ineligible perhaps for a Chapter 7, so we tell them that if they want relief from the bankruptcy code, they’ve got to file a Chapter 13 and offer this disposable income to their creditors.

Q: What happens if that disposable income figure turns out to be zero or just a couple of dollars?

CH: They really wouldn’t flunk the means test in that case. There’s an algorithm in the computer program that looks at what’s left over at the end of the month and what their debt is, and it figures out if you have an ability to pay back a certain percentage of that debt. The program indicates whether they’ve flunked or passed the test; it shows if you’re eligible for a Chapter 7. Sometime you can get around that, because we’re looking at income over the past six months. If the debtor has just lost a job and no longer has that income, we can override the test in a way, or at least show this special circumstance—they’re now destitute and don’t have any money—they’re not required to pay back some of this debt when clearly they don’t have an ability to do that.

Q: So that inability to pay back the debt determines whether you file for Chapter 7 or Chapter 13?

CH: Right. Most people will file for Chapter 7, wipe the slate clean, not make any monthly payments, and be done in three to four months. In Chapter 13, it’s three to five years where they’re making this monthly payment to a Chapter 13 trustee who then divvies up the money amongst the creditors in a certain way. Some people do Chapter 13 because they need it to save a house, to pay taxes, or do some other creative things, but there’s a small percentage of people who are required to file Chapter 13 because they are too rich to just wipe the slate clean. It’s not fair; it’s consider an abuse of the bankruptcy code for somebody who makes $100,000 to just get rid of all their debt.

Q: So that medium income is the number that determines whether you makes too much money?

CH: Right. It’s a starting point. If they’re below that number, they pass automatically. If they’re above that number, then we have to do this more-comprehensive test that looks at not just gross income, but where all of that money goes. Taxes, insurance, rent, food, utilities, car payments, student loans—all of those things. Then, after you plug in all of these numbers, the program shows a green happy face if you pass or a yellow unhappy face if you fail.

There’s a case we filed in which we received the green happy face. We filled in the debtor’s average monthly income and then on the next page it totals it up to $62,580. The median income for a family of this size is $62,431. So, because their combined income was a little bit above the median income, I had to go through the program and fill in additional fields, for example car payments and mortgage payments. There are certain standards, for example for a two-person household with two cars it’s $424 per month for gas, oil, and routine maintenance on a vehicle. At the very bottom of this test, in this particular case, we come up with this number for Disposable Monthly Income, which we call “DMI” and here it’s “minus $371.” So, clearly in this case they don’t have any money left over. That’s why the program gives us the green happy face, because it concluded that even though their income is above median income, because of all of their expenses, there is no money left over for the creditors. So they qualify for Chapter 7. Now if this had been a yellow unhappy face, and the DMI had been a significant positive number, then we would have to say to the debtor that the case would get thrown out or threatened with dismissal, so we just know that we have to file as a Chapter 13. Then they’re in this plan for 60 months, five years, to pay back as much of their debt as possible.

JS: And there are certain things that are not deductible on a Chapter 7 means test that are deductible on a Chapter 13 means test.

Q: Such as?

JS: Such as retirement account contributions or 401(k) loan repayments. Going back to the Social Security issue, the code says that, if you have a habit of making retirement contributions, you’re supposed to be able to continue those under this means test. Then you put your budget together going forward. Our associate Andrew DeYoung had a case where he tried to schedule the ongoing contributions, because she had done them within the six months. But he received a creditor objection and Judge Graham said, “I’m not going to allow you to keep socking away this kind of money while paying very little on your debt.

CH: Even though they’re in a Chapter 13, they get credit for it.

JS: Correct. She had a very low Disposable Monthly Income number under the means test, but when it came before the judge, the judge said this doesn’t pass the smell test. If the client were to appeal, maybe the client would have won, but the client didn’t have the resources to appeal.

Q: Was it because the IRA contribution was too high?

JS: It was substantial. Plus, evidence came out that the debtor worked for a university. If she contributed some phenomenal amount of money, her employer would match it with about 20% of the contribution. So this woman was trying to put away $9000 to $10,000 a year, hoping to get another $3000 to $4000 match. It was not the trustee who objected, it was an individual creditor who had loaned the debtor money and who spent enormous resources objecting to the proposed plan. I don’t know that every judge would have sided with the creditor, but this particular one did.

Q: So the judge threw out the IRA contribution entirely or forced her to lower the payment?

JS: She was in a Chapter 13, so the plan Andrew offered met the means test. But the creditor started objecting with old law—pre-2005 case law—and Andrew and I did not believe the creditor could win because it was such old case law.

CH: But it was an extraordinary amount of her income that she was contributing.

JS: Yes, it was about 15%, so a substantial portion of her income was being deferred.

CH: I’ve told people that if their contribution is 4%, or 6%, or even 8%, that no one is going to squawk. But if it’s 10% or more, that’s probably where it wouldn’t pass the smell test.

JS: In this case, the debtor was trying to only pay about $7000 on over $100,000 debt, so the judge said, “You’re not going to walk out of here with a fat 401(k).”

CH: This case illustrates the situation where you go to law school and think the law is black and white. You’re going to learn how to solve problems and there are definite rules. But the law is actually shades of gray. It’s almost never black and white. One judge might say, “That seems reasonable,” and another judge might say “It’s unreasonable.” It’s unpredictable, especially in state court law, where you go to one county and have one judge rule one way, then you go to another county, with the exact same facts, and another judge might rule a different way. Clients always ask, “Can you predict the results?” But that’s next to impossible, because you just don’t know how that judge on that day is going to interpret those facts in light of the law. Sometimes I’ve had judges where it was not what they knew that I was afraid of, it was what they knew that just wasn’t so. They thought that they knew the law, but they didn’t and they interpreted the law improperly. But you can’t go to the judge and imply they’re wrong. The only way you can do that is to appeal and most people we represent don’t have the financial ability or resources to appeal a decision, because that’s really expensive and time-consuming. The case mentioned earlier is a good example of the gray shades of the law and it’s fluidity, because by offering a plan with only a $250 monthly payment, instead of $660 a month, Andrew saved our client $24,600 over the life of the five-year plan.

Part 2 of Conversation: Differences Between Chapter 7 Bankruptcy and Chapter 13 Bankruptcy

Part 3 of Conversation: Divorce and Child Support Can Impact a Bankruptcy

Part 4 of Conversation: Being Discharged From Bankruptcy